Media shocked to learn 'global intifada' means killing people around the globe

Harvard upgrades antisemitism from 'unfounded concern' to 'complex context'

University officials condemn violence, urge students to avoid 'harmful specificity,' 'jumping to adjectives,' 'noticing patterns,' or 'assigning motives' to motives

NPR rebrands antisemitism as 'community tensions,' adds somber piano music

Anchor: hate is wrong, but also 'understandable' under certain editorial guidelines

Panel concludes “from the river to the sea” refers to nature hikes and inclusive trail access

Experts: free speech safest when pre-approved

Manhattan renamed 'They-hattan'; Madison Avenue apologizes for misgendering itself

As media accuse ICE of cruelty, Ukraine wonders if returning Russians to Russia is culturally insensitive

Epstein files don mustache and sombrero combo; Democrats praise 'cultural enrichment'

NPR unveils new game show: 'Wait-wait… don’t deport me!'

Progressive experts alarmed: troops may now be ordered to engage the enemy, not identify as it

New American Pope to host first-ever Vatican tailgate

New American Pope to host first-ever Vatican tailgate

American Pope’s first tweet: “Just got off the phone with Jesus. Huge stuff coming.”

This day in alternative history: Federal district court judge blocks President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation Executive Order

The mains in Spain fail mainly under strain

Kamala Harris to lead task force on understanding what she just said

Cool Trends: The trans child has replaced the Louis Vuitton handbag as suburban status symbol

Teachers’ Union Manual redefines the three Rs as Racism, Reparations, and Rioting

Once the Trans-Visibility Easter Sunday is over, Biden to declare the rest of 2024 National Forgiveness of Bribery and Influence Peddling Year

The Pope concedes Lucifer's win, hoists a white flag over the Vatican

TPC Study: If all cultures are equal, no one needs asylum

Due to EV cold-weather issues, EPA orders winter migration south for all northern state residents

Due to EV cold-weather issues, EPA orders winter migration south for all northern state residents

WH economists forecast 2024 will feel like a recession but assure it's not

And just like that, COEXIST bumper stickers disappear, replaced with GENOCIDE bumper stickers.

Negotiations fail to pause hostilities between the Biden administration and America

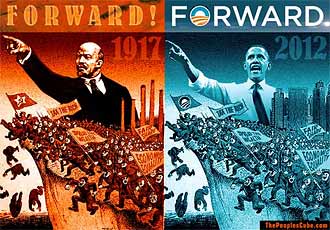

Joe Biden’s talks with China lead to new national program, ‘The Great Leap Backwards’

Dear Democrats: 1930s Germany called; they want their antisemitism back

Community organizers: We are all in this together until you are of no further use.

TIME magazine names Hamas World's Most Sexy Murderers, Rapists, Sadistic Torturers

Mideast crisis: Gaza hospitals running out of rocket launchers and human shields

Climate activists: you are the carbon we want to reduce

Democrats to cancel Chicago Convention; replace it with all mail-in ballots

Hamas request permanent cease-fire in Oakland, CA

Bad weather causes President Biden to proclaim National Political Emergency

School cancels course on Critical Critical Studies that used Critical Studies methodology to examine Critical Studies

News you can use: CBSABCNBCCNNMSNBC+ is trans-truth and demands the right to be truth

Breaking: Thousands of new Chinese spy balloons fly over U.S., painted with Biden 2024 campaign posters

New rule: calling Chinese spy balloons “Chinese” is deemed racist

Breaking: Biden promises to shoot down Chinese spy balloon as soon as it gets as high as Hunter

Hurricane Update: Fears arise that Gov. Ron DeSantis may reroute Hurricane Ian from Florida coast to Martha's Vineyard

Hurricane Update: Fears arise that Gov. Ron DeSantis may reroute Hurricane Ian from Florida coast to Martha's Vineyard

Study: People who define themselves by what they stand against, are usually afraid to tell people what they stand for

Liz Cheney: Voters need to ask themselves, why they are so out of touch with their politicians

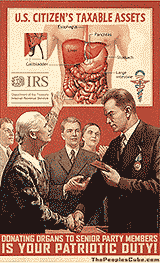

White House: IRS toy guns for children are now politically correct, mandatory

BREAKING: Biden's economic sanctions on the U.S. to be partially lifted prior to November election

GOP's new slogan for midterms: Make Dissent Patriotic Again

GOP's new slogan for midterms: Make Dissent Patriotic Again

PSA: Due to high gas prices police departments will now be responding and making arrests via Zoom.

NYT: Roe vs Wade to be renamed the "Don't Say Fetus" law

Democrats insist on carrying unwanted presidency to term

Elon Musk went to bed thinking he owns Twitter. Then the mail-in ballots arrived at 2am...

Obama: "If you like your information you can keep your information"

Obama: "If you like your information you can keep your information"

Fact checkers reveal Biden handler not a real Easter bunny

Biden 2021: you'll save $0.16 on 4th of July BBQ!

Biden 2022: you'll save a ton of $$ if you don't eat this 4th of July!

Disney to buy Epstein Island for new theme park

The Biology Underground is like the Weather Underground, except they are real biologists and they've had to go underground

"Psssst. Hey you, kid. Ya wanna watch a Disney movie with me?"

"I am not suicidal," says COVID-19 after being contracted by Hillary Clinton

Trans-swimmer Lia Thomas's trophy is smaller than for male swimmers, and only 73% gold

Sources: U.S. now considers majority of U.S. citizens a threat to U.S.

BREAKING: Russian General claims he was beaten up outside Ukrainian bio lab by two Nazis who poured vodka and caviar over him and yelled "This is NATO Country!"

Global warming news: 100,000 Russian migrants fleeing climate change about to march into Ukraine

Future headline: Donald Trump to buy CNN for one dollar

Georgia Governor Stacy Abrams feels honored to be the new Supreme Court justice

President Biden: 'Vote for me or I'll shoot this foot'

Fact checkers give Pinocchio's speech four Bidens

Fauci: The only thing we have to fear, is a lack of fear itself!

Study: Most people have had sex more violent than January 6th

Facebook permanently bans Facebook from Facebook for violating Facebook community standards

Facebook permanently bans Facebook from Facebook for violating Facebook community standards

New remake of the 1950's horror movie Them to be titled Them/They

Teachers Union: Idea that CRT is being taught in K-12 just a conspiracy theory by white supremacists trying to maintain their systemically racist police state

Xze/She/He who controls the past controls the future; Xze/She/He who controls the present controls the past

S ocialists vow to fight against Critical Socialism Theory

ocialists vow to fight against Critical Socialism Theory

A more perfect Soviet Union: the Party pretends it unites us, and we pretend we are united

Biden solves border crisis with free direct flights from Central America to major metropolitan areas

Critical race theory: destroy the world of systemic racism, build a world of systemic race-baiting

Critical race theory: destroy the world of systemic racism, build a world of systemic race-baiting

In the future everyone will get canceled for fifteen minutes

Biden proposes bill to spend two trillion dollars on more money printing factories

Social unity: They pretend to hold elections and we pretend we voted

Immigrants to Texas and Florida from New York and California break down and cry when they realize all their sacrifices for a better tomorrow were based on lies

Immigrants to Texas and Florida from New York and California break down and cry when they realize all their sacrifices for a better tomorrow were based on lies

China anal swabs detect new 'silent but deadly' transmission of covid-19 variant

Social science breakthrough: 'White' is the new way of saying 'Bourgeois'

Biden administration swat teams make sweeping arrests of underground female-only track meets

'Green energy' to be renamed 'blackout energy' for easier comprehension of climate complexities

New children's game: Rock, Paper, Scissors, Science

Texas: Biden administration sends emergency wind turbines to help fight the blackouts

BREAKING: Biden signs executive order canceling the number 45

ATTENTION: It is your duty to report anyone who says this is no longer a free country. Fact-checking commissars are monitoring all state-approved social media platforms for your convenience

OUT: If you don't vote, you can't complain!

IN: If you didn't vote Democrat, you can't complain!

Social media justice: followers removed from pro-Trump accounts will be added to Biden's Twitter account

Fact check: a democratic election is the one in which votes are counted until Democrats win

JUST IN: China bans Twitter for being too totalitarian

Pelosi introduces new House rule to replace 'gender' terms like mother, daughter, father, son with the word 'comrade'; the only acceptable pronoun will also be 'comrade'

Sources: Biden transition team demands access to White House basement to begin renovations

BREAKING: President Trump pardons America for its past

Prime Minister Modi: to avoid accusations of racism India will change its name to Cleveland

Biden creates Antifascist Librarian Justice Committee; the first book scheduled for burning is Fahrenheit 451

Media study: 148% of Americans believe voter fraud doesn't exist

Media study: 148% of Americans believe voter fraud doesn't exist

2020 Election forecast: if Joe Biden emerges from the basement on Election Day and sees his shadow, expect four more years of Trump

BREAKING: President Trump pardons Corn Pop

Toobin, though on administrative leave, is still pulling for Biden

Chinese whistleblower: Biden-20 was genetically engineered in a Wuhan lab

Chinese whistleblower: Biden-20 was genetically engineered in a Wuhan lab

Nancy Pelosi sponsors a bill to create the office of removal of the President

New college humanities major: Critical Trump Studies

Opinion: Joe Biden is just an idea

CNN: Biden took a solid second place in the debate, while Trump only came next to last

Having ordered that all Californians switch to electric cars by 2035, Gov. Gavin Newsom follows up by mandating them to have electricity by 2035

Election 2020: Joe Biden pledges to a peaceful post-election transfer of power to George Soros

Out: Flatten the curve. In: Flatten the country.

Breaking: the Democrat Party has finished transitioning from being the party of JFK to being the party of Lee Harvey Oswald

Paradigm shift in Chromatics: Study shows Indigo (#3F00FF) mixed with Jamaic (#C0FF01) yields Black (#000000)

Study: the trouble with wokeism is eventually you run out of victims

Study: the trouble with wokeism is eventually you run out of victims

Stacey Abrams refuses to concede to Harris; declares herself Biden's VP

Election 2020: Spunky former presidential candidate wins VP slot by a head

Churches in many states to hold services in opened up pubs and bars

Election 2020: Xi Jinping still undecided on vice president for Joe Biden

Reports: Republicans pounce on 'Republicans pounce' reports

Reports: Republicans pounce on 'Republicans pounce' reports

Minneapolis launches online looting app to combat Covid-19

DNC study finds lockdowns no longer necessary as the economy is now being destroyed more effectively by looters and rioters

With America in lockdown, China offers to host Democrat primary

Bernie Sanders tests negative for President

In related news, Joe Biden follows other candidates in withdrawing from race and endorsing Joe Biden

New York Governor Cuomo shuts down all 'non-essential' business, surprised to find himself out of a job

Biden commits to picking a woman as running mate as long as she passes his sniff test

Biden commits to picking a woman as running mate as long as she passes his sniff test

Joe Biden's coronavirus prevention tips: always rub hand sanitizer on young girls before sniffing and fondling them

Russian lawmakers warned that the American Democrats are meddling to re-elect Putin

Joe Biden promises lucrative board member jobs as door prizes to get people to his rallies

Democrats now worried they might even lose the illegal alien vote

Democrats now worried they might even lose the illegal alien vote

Soleimani's remains FedExed back to Iran and now no one knows what happened to the box

BREAKING: massive search underway in Iran after Soleimani's boxed FedEx'd remains stolen off front porch

Liz Warren harshly critical of Biden's suggestion to coal miners that they should learn to code, offers to have them trained as romance novelists instead

Pelosi: "First we have to impeach Donald Trump before we can find out why we impeached him."

Pelosi: "First we have to impeach Donald Trump before we can find out why we impeached him."

Schiff calls his Amazon Alexa to testify: 'She knows absolutely everything'

Iran answers to new Reagan statue in Berlin by erecting Obama statue at Tehran airport where he delivered pallets of cash

California accepts award for most progressive environmental policies; further progressive developments to be announced as blackouts permit

BREAKING: Romney DNA test reveals he is 1/1024th Republican

California Governor Gavin Newsom blames electricity blackouts on Ukrainian kulaks, vows revenge

California Governor Gavin Newsom blames electricity blackouts on Ukrainian kulaks, vows revenge

Rat falling from White House ceiling fears for his life, begs reporters for protection, offers a tell-all memoir

Latest UN climate report shows this month so far has seen the scariest climate pronouncements on record

Climate science: there's no need for climate protests in China because China is already communist

Islamic clerics split on whether Reps. Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib should be traveling around the world without an accompanying male relative

Islamic clerics split on whether Reps. Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib should be traveling around the world without an accompanying male relative

Dem candidates call for the Beatles' song 'Get Back' and the 'White Album' to be banned; surviving two white guys of the group must pay reparations

Bond's number is up: next 007 will be a black woman, played by Barack Obama

NYT: moon landing was one small step for Man, one giant leap for White Male Supremacy

HURRICANE WATCH: Tropical storm Barry has records sealed, once offshore expected to change name to Barack

Trump politicizes the 4th of July, declares it henceforth to be called the 45th of July, or July the Trumpth

Barack Obama critical of Trump for failing to insert 'I, me, my' into his 4th of July speech: "very unpresidential!"

Congressional Democrats: John Dean's testimony proves Trump is Nixon in disguise and must be impeached

Bernie Sanders admits to being a millionaire, promises to eat himself if nominated

International Women's Day observed, women only paid 73% of attention afforded to men

International Women's Day observed, women only paid 73% of attention afforded to men

Democrats: anti-Semitism means never having to say you're sorry

AOC: aborting babies helps preserve the planet for the next generation

Bernie Sanders launches presidential campaign, promises to "build a great big beautiful Iron Curtain" around America if elected

West Virginia renames itself Eastern Kentucky to avoid further embarrassment from Virginia

West Virginia renames itself Eastern Kentucky to avoid further embarrassment from Virginia

BREAKING: Justice Ginsburg released from hospital after breaking 3 ribs at late night bar brawl in Adams Morgan

DNA news: Senator Warren tanking in latest totem polls

Orwell studies: 84% of academics believe problems raised in 1984 can be fixed with solutions from Animal Farm

Progress in gender justice: online dating industry issues recommendations for men to wear body cameras, bring attorneys as chaperones

Progress in gender justice: online dating industry issues recommendations for men to wear body cameras, bring attorneys as chaperones

Study: the only people who don't know what socialism is are the socialists

Poll: 1 in 3 #FightFor15 activists believe movement is related to lowering the age of consent across America

CNN expert: Kavanaugh confirmation will increase global warming by 3 degrees

Harry Reid comes forth to say Judge Kavanaugh didn't pay any taxes in high school

Hollywood to America: If you've got a flag on the Moon, you didn't plant that; some other country made that happen

Protest march in straight jackets against Trump ends in chaos as participants try but fail to free themselves

HEADLINES YOU WILL NEVER SEE: California Gov. Jerry Brown single-handedly stops wildfires in his state by issuing an immediate statewide ban on wildfires

San Francisco closes all Planned Parenthood clinics after sting operation catches employees using plastic straws

Vegan mother undergoes experimental surgery to force her breasts to produce almond milk

With none of his emails answered, frustrated Nigerian man commits suicide and leaves $100bn fortune to charity

California gives new meaning to strawman argument as caped Strawman battles supervillains in restaurants, bars, and fast food joints

Violence increases in Mexico as cartels switch from smuggling drugs to plastic straws to San Francisco

Obama proposes a Paris Economic Change agreement among nations to address how world will cope with future runaway economic warming

Stormy Daniels plans border visit to give migrant children freebies

San Francisco: man dumping off 20 lbs of human waste in plastic bag on street corner cited for using non-biodegradable plastic bag

BREAKING: ICE renamed Planned Citizenship, immediately absolving it of all criticism

Senate Democrats demand Supreme Court nominee not be unduly influenced by U.S. Constitution

BREAKING: In 2018, Obama and Biden can finally celebrate Recovery Summer

IG Report: the FBI broke the law, but since there was no criminal intent, no reasonable prosecutor would bring such a case

IG Report: the FBI broke the law, but since there was no criminal intent, no reasonable prosecutor would bring such a case

Pelosi on Trump's MS-13 "animals" comments: "Four legs good, two legs bad"

Iran nuclear talks set to resume between the United States and John Kerry

Report: The Mueller investigation has finally determined that the lyrics to Louie Louie are not about Trump and Russian collusion

MARKETS: Demand for carbon credits spikes as Hamas seeks to undo damage to Earth's atmosphere caused by burning 10,000 tires on Gaza border

MARKETS: Demand for carbon credits spikes as Hamas seeks to undo damage to Earth's atmosphere caused by burning 10,000 tires on Gaza border

BREAKING: After state reassignment surgery Pennsylvania will henceforth be known as Transylvania

Experts: If we don't act now, unicorns will be extinct in just ten years. Children will ask, "Mommy, what's a unicorn?" Women and minorities will be forced to seek alternative hallucinations

Experts: If we don't act now, unicorns will be extinct in just ten years. Children will ask, "Mommy, what's a unicorn?" Women and minorities will be forced to seek alternative hallucinations

Korean war must continue: Hawaiian federal judge declares Trump's peace effort unconstitutional

New York: feminists march on Broadway, demand the street be given new, non-misogynistic name

Experts: California's planned transition of all state jobs from citizens to illegal aliens by 2020 will help to avoid bankruptcy and save money for social programs for illegal aliens

Experts: California's planned transition of all state jobs from citizens to illegal aliens by 2020 will help to avoid bankruptcy and save money for social programs for illegal aliens

Putin: If I didn't want Hillary to be president she would be dead

Doritos maker PepsiCo to introduce snack line for women; new Doritas™ chips will be 77% as big as Doritos and won't make any scary 'crunchy noises'

TMZ: Tooth Fairy accused of sexually assaulting millions of children, outs self as Transgendered Tooth Recovery Specialist

RUSSIA COLLUSION: Trump offers Putin to trade Rep. Maxine Waters for two unnamed members of the State Duma

Ikea founder dead at 91; his coffin arrived in a box with confusing instructions and took 3 hours to assemble

This Thanksgiving ex-president Obama continues with his tradition of apologizing to turkeys everywhere for the injustice they suffered since America's founding

Oslo, Norway: 2017 Nobel Peace Prize goes to advocacy group about which you'll forget immediately after reading this headline

Oslo, Norway: 2017 Nobel Peace Prize goes to advocacy group about which you'll forget immediately after reading this headline

Cambridge, MA, library to replace racist 'Cat in the Hat' with inclusive 'Che in a Beret'

Millions of men worldwide eagerly await broadcast of Hugh Hefner's funeral, solely for the articles

Bill Gates offers to pay for Trump's wall on condition he gets to install Windows

Bernie Sanders introduces single-payer public transportation bill to end America's unequal, unfair, and expensive private transportation system

Bernie Sanders introduces single-payer public transportation bill to end America's unequal, unfair, and expensive private transportation system

DNC embroiled in controversy after official Twitter account accidentally 'likes' pictures of US Constitution and Bill of Rights

Hurricane Irma hits Cuba, causes millions of dollars worth of improvements to property and infrastructure

Climate study: extreme weather may be caused by unlicensed witches casting wrong spells in well-meaning effort to destroy Trump

Ex-president Obama declares Irma "Hurricane of Peace," urges not to jump to conclusions and succumb to stormophobia

CNN: Trump reverses Obama's executive order banning hurricanes

ISIS claims responsibility for a total solar eclipse over the lands of American crusaders and nonbelievers

When asked if they could point to North Korea on a map many college students didn't know what a map was

CNN: We must bring America into the 21st century by replacing the 18th century Constitution with 19th century poetry

Pelosi: 'We have to impeach the president in order to find out what we impeached him for'

BREAKING: As of Saturday July 8, 2017, all of Earth's ecosystems have shut down as per Prince Charles's super scientific pronouncement made 96 months ago. Everything is dead. All is lost. Life on Earth is no more.

DNC to pick new election slogan out of four finalists: 'Give us more government or everyone dies,' 'Vote for Democrats or everyone dies,' 'Impeach Trump or everyone dies,' 'Stop the fearmongering or everyone dies'

Al Gore's "An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power" is humanity's last chance to save the Earth before it ends five years ago

Al Gore's "An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power" is humanity's last chance to save the Earth before it ends five years ago

Experts: The more we embrace diversity the more everything is the same

BOMBSHELL: TMZ offers Kathy Griffin $5 mil to keep any future sex tape private

DEVELOPING: CNN, WaPo, NYT anonymous sources say Vladimir Putin may have ties to Russia

BREAKING: Manning and Snowden have come out with strong condemnation of Donald Trump leaking classified information to Russia

Gun store goes into lockdown over report an "active university professor" roving the grounds

Dozens injured at Ralph Lauren & Louis Vuitton headquarters after Ivanka calls in missile strikes on rival fashion houses

BOMBSHELL: Evidence proves Donald Trump conspired with his campaign to defeat Hillary Clinton

University ranked "very intolerant of free speech" fights the accusation by banning the study and all involved

Concerned that Russians don't consume enough alcohol in the month of March, Russia's Orthodox Church makes St. Patrick's Day official holiday

Grassroots group calls for "The Million Regulators March" on Washington, supported by all who fear the loss of their betters telling them what to do

Experts: Starbucks CEO Schultz's hiring of 10,000 Muslim refugees likely to blow up in his face

Will the groundprog be frightened by its own shadow and hide - or will there be another season of insane protests?

Will the groundprog be frightened by its own shadow and hide - or will there be another season of insane protests?

Trump signs executive order making California and New York national monuments; residents have two days to vacate

Women's March against fascism completed with 400,000 fewer deaths than anticipated

Women's March against fascism completed with 400,000 fewer deaths than anticipated

Feminist historians uncover ghastly concentration camps where so-called "housewives" were forced to live inauthentic lives slaving away in kitchens

Dictionary of the future: Global Warming was a popular computer simulation game, where the only way to win was not to play

"Anti-fascist" groups violently protest misspelling of their original name, "aren't-we-fascists"

Post-inauguration blues: millions of democrats distraught as the reality of having to find real jobs sets in

Post-inauguration blues: millions of democrats distraught as the reality of having to find real jobs sets in

"Journalism is the continuation of war by other means" is exposed as a fake quote by mainstream media journalists

Congressional Democrats: "We cannot just simply replace Obamacare with freedom because then millions of Americans will suddenly become free"

Schoolchildren jailed for building only white snowmen

Obama's reckless attacks on Russia serve as recruitment tool to create more Russian hackers

Hillary: "I lost, so I'm going to follow our democratic traditions, poison the wells, and scorch the earth"

Children in Venezuela cook and eat their Christmas toys

Hillary: "I can hack Russia from my bathroom"

Hillary suggests to counter "fake news" with government newspaper called "Truth" ("Pravda" for Russian speakers)

BREAKING: Millions of uncounted votes found on Hillary's private voting machine in her Chappaqua bathroom

BREAKING: Millions of uncounted votes found on Hillary's private voting machine in her Chappaqua bathroom

New York Times: Fidel Castro world's sexiest corpse

After years of trial and error, CIA finally succeeds with the "waiting it out" technique on Fidel Castro

Post-election shopping tip: look for the PoliticsFree label at your local grocer to make sure you don't buy from companies that don't want your business anymore

Post-election shopping tip: look for the PoliticsFree label at your local grocer to make sure you don't buy from companies that don't want your business anymore

In Hillary's America, email server scrubs you

Obama transfers his Nobel Peace Prize to anti-Trump rioters

Democrats blame Hillary's criminal e-mail server for her loss, demand it face prison

Afraid of "dangerous" Trump presidency, protesters pre-emptively burn America down to the ground

Afraid of "dangerous" Trump presidency, protesters pre-emptively burn America down to the ground

Clinton Foundation in foreclosure as foreign donors demand refunds

Hillary Clinton blames YouTube video for unexpected and spontaneous voter uprising that prevented her inevitable move into the White House

Sudden rise in sea levels explained by disproportionately large tears shed by climate scientists in the aftermath of Trump's electoral victory

FBI director Comey delighted after receiving Nobel Prize for Speed Reading (650,000 emails in one week)

U.N. deploys troops to American college campuses in order to combat staggeringly low rape rates

Responding to Trump's surging poll numbers, Obama preemptively pardons himself for treason

Following hurricane Matthew's failure to devastate Florida, activists flock to the Sunshine State and destroy Trump signs manually

Tim Kaine takes credit for interrupting hurricane Matthew while debating weather in Florida

Study: Many non-voters still undecided on how they're not going to vote

The Evolution of Dissent: on November 8th the nation is to decide whether dissent will stop being racist and become sexist - or it will once again be patriotic as it was for 8 years under George W. Bush

Venezuela solves starvation problem by making it mandatory to buy food

Breaking: the Clinton Foundation set to investigate the FBI

Obama captures rare Pokémon while visiting Hiroshima

Movie news: 'The Big Friendly Giant Government' flops at box office; audiences say "It's creepy"

Movie news: 'The Big Friendly Giant Government' flops at box office; audiences say "It's creepy"

Barack Obama: "If I had a son, he'd look like Micah Johnson"

White House edits Orlando 911 transcript to say shooter pledged allegiance to NRA and Republican Party

President George Washington: 'Redcoats do not represent British Empire; King George promotes a distorted version of British colonialism'

Following Obama's 'Okie-Doke' speech, stock of Okie-Doke soars; NASDAQ: 'Obama best Okie-Doke salesman'

Weaponized baby formula threatens Planned Parenthood office; ACLU demands federal investigation of Gerber

Experts: melting Antarctic glacier could cause sale levels to rise up to 80% off select items by this weekend

Travel advisory: airlines now offering flights to front of TSA line

As Obama instructs his administration to get ready for presidential transition, Trump preemptively purchases 'T' keys for White House keyboards

John Kasich self-identifies as GOP primary winner, demands access to White House bathroom

Upcoming Trump/Kelly interview on FoxNews sponsored by 'Let's Make a Deal' and 'The Price is Right'

News from 2017: once the evacuation of Lena Dunham and 90% of other Hollywood celebrities to Canada is confirmed, Trump resigns from presidency: "My work here is done"

Non-presidential candidate Paul Ryan pledges not to run for president in new non-presidential non-ad campaign

Trump suggests creating 'Muslim database'; Obama symbolically protests by shredding White House guest logs beginning 2009

National Enquirer: John Kasich's real dad was the milkman, not mailman

National Enquirer: Bound delegates from Colorado, Wyoming found in Ted Cruz’s basement

Iran breaks its pinky-swear promise not to support terrorism; US State Department vows rock-paper-scissors strategic response

Women across the country cheer as racist Democrat president on $20 bill is replaced by black pro-gun Republican

Federal Reserve solves budget crisis by writing itself a 20-trillion-dollar check

Widows, orphans claim responsibility for Brussels airport bombing

Che Guevara's son hopes Cuba's communism will rub off on US, proposes a long list of people the government should execute first

Che Guevara's son hopes Cuba's communism will rub off on US, proposes a long list of people the government should execute first

Susan Sarandon: "I don't vote with my vagina." Voters in line behind her still suspicious, use hand sanitizer

Campaign memo typo causes Hillary to court 'New Black Panties' vote

New Hampshire votes for socialist Sanders, changes state motto to "Live FOR Free or Die"

Martin O'Malley drops out of race after Iowa Caucus; nation shocked with revelation he has been running for president

Statisticians: one out of three Bernie Sanders supporters is just as dumb as the other two

Statisticians: one out of three Bernie Sanders supporters is just as dumb as the other two

Hillary campaign denies accusations of smoking-gun evidence in her emails, claims they contain only smoking-circumstantial-gun evidence

Obama stops short of firing US Congress upon realizing the difficulty of assembling another group of such tractable yes-men

Obama stops short of firing US Congress upon realizing the difficulty of assembling another group of such tractable yes-men

In effort to contol wild passions for violent jihad, White House urges gun owners to keep their firearms covered in gun burkas

TV horror live: A Charlie Brown Christmas gets shot up on air by Mohammed cartoons

Democrats vow to burn the country down over Ted Cruz statement, 'The overwhelming majority of violent criminals are Democrats'

Democrats vow to burn the country down over Ted Cruz statement, 'The overwhelming majority of violent criminals are Democrats'

Russia's trend to sign bombs dropped on ISIS with "This is for Paris" found response in Obama administration's trend to sign American bombs with "Return to sender"

University researchers of cultural appropriation quit upon discovery that their research is appropriation from a culture that created universities

University researchers of cultural appropriation quit upon discovery that their research is appropriation from a culture that created universities

Archeologists discover remains of what Barack Obama has described as unprecedented, un-American, and not-who-we-are immigration screening process in Ellis Island

Mizzou protests lead to declaring entire state a "safe space," changing Missouri motto to "The don't show me state"

Mizzou protests lead to declaring entire state a "safe space," changing Missouri motto to "The don't show me state"

Green energy fact: if we put all green energy subsidies together in one-dollar bills and burn them, we could generate more electricity than has been produced by subsidized green energy

State officials improve chances of healthcare payouts by replacing ObamaCare with state lottery

NASA's new mission to search for racism, sexism, and economic inequality in deep space suffers from race, gender, and class power struggles over multibillion-dollar budget

College progress enforcement squads issue schematic humor charts so students know if a joke may be spontaneously laughed at or if regulations require other action

College progress enforcement squads issue schematic humor charts so students know if a joke may be spontaneously laughed at or if regulations require other action

ISIS opens suicide hotline for US teens depressed by climate change and other progressive doomsday scenarios

Virginia county to close schools after teacher asks students to write 'death to America' in Arabic

Virginia county to close schools after teacher asks students to write 'death to America' in Arabic

'Wear hijab to school day' ends with spontaneous female circumcision and stoning of a classmate during lunch break

ISIS releases new, even more barbaric video in an effort to regain mantle from Planned Parenthood

Impressed by Fox News stellar rating during GOP debates, CNN to use same formula on Democrat candidates asking tough, pointed questions about Republicans

Impressed by Fox News stellar rating during GOP debates, CNN to use same formula on Democrat candidates asking tough, pointed questions about Republicans

Shocking new book explores pros and cons of socialism, discovers they are same people

Pope outraged by Planned Parenthood's "unfettered capitalism," demands equal redistribution of baby parts to each according to his need

Pope outraged by Planned Parenthood's "unfettered capitalism," demands equal redistribution of baby parts to each according to his need

John Kerry accepts Iran's "Golden Taquiyya" award, requests jalapenos on the side

Citizens of Pluto protest US government's surveillance of their planetoid and its moons with New Horizons space drone

John Kerry proposes 3-day waiting period for all terrorist nations trying to acquire nuclear weapons

John Kerry proposes 3-day waiting period for all terrorist nations trying to acquire nuclear weapons

Chicago Police trying to identify flag that caused nine murders and 53 injuries in the city this past weekend

Cuba opens to affordable medical tourism for Americans who can't afford Obamacare deductibles

State-funded research proves existence of Quantum Aggression Particles (Heterons) in Large Hadron Collider

State-funded research proves existence of Quantum Aggression Particles (Heterons) in Large Hadron Collider

Student job opportunities: make big bucks this summer as Hillary’s Ordinary-American; all expenses paid, travel, free acting lessons

Experts debate whether Iranian negotiators broke John Kerry's leg or he did it himself to get out of negotiations

Experts debate whether Iranian negotiators broke John Kerry's leg or he did it himself to get out of negotiations

Junior Varsity takes Ramadi, advances to quarterfinals

US media to GOP pool of candidates: 'Knowing what we know now, would you have had anything to do with the founding of the United States?'

NY Mayor to hold peace talks with rats, apologize for previous Mayor's cowboy diplomacy

NY Mayor to hold peace talks with rats, apologize for previous Mayor's cowboy diplomacy

China launches cube-shaped space object with a message to aliens: "The inhabitants of Earth will steal your intellectual property, copy it, manufacture it in sweatshops with slave labor, and sell it back to you at ridiculously low prices"

Progressive scientists: Truth is a variable deduced by subtracting 'what is' from 'what ought to be'

Progressive scientists: Truth is a variable deduced by subtracting 'what is' from 'what ought to be'

Experts agree: Hillary Clinton best candidate to lessen percentage of Americans in top 1%

America's attempts at peace talks with the White House continue to be met with lies, stalling tactics, and bad faith

Starbucks new policy to talk race with customers prompts new hashtag #DontHoldUpTheLine

Hillary: DELETE is the new RESET

Hillary: DELETE is the new RESET

Charlie Hebdo receives Islamophobe 2015 award; the cartoonists could not be reached for comment due to their inexplicable, illogical deaths

Russia sends 'reset' button back to Hillary: 'You need it now more than we do'

Russia sends 'reset' button back to Hillary: 'You need it now more than we do'

Barack Obama finds out from CNN that Hillary Clinton spent four years being his Secretary of State

President Obama honors Leonard Nimoy by taking selfie in front of Starship Enterprise

Police: If Obama had a convenience store, it would look like Obama Express Food Market

Study finds stunning lack of racial, gender, and economic diversity among middle-class white males

Study finds stunning lack of racial, gender, and economic diversity among middle-class white males

NASA: We're 80% sure about being 20% sure about being 17% sure about being 38% sure about 2014 being the hottest year on record

People holding '$15 an Hour Now' posters sue Democratic party demanding raise to $15 an hour for rendered professional protesting services

People holding '$15 an Hour Now' posters sue Democratic party demanding raise to $15 an hour for rendered professional protesting services

Cuba-US normalization: US tourists flock to see Cuba before it looks like the US and Cubans flock to see the US before it looks like Cuba

White House describes attacks on Sony Pictures as 'spontaneous hacking in response to offensive video mocking Juche and its prophet'

CIA responds to Democrat calls for transparency by releasing the director's cut of The Making Of Obama's Birth Certificate

Obama: 'If I had a city, it would look like Ferguson'

Biden: 'If I had a Ferguson (hic), it would look like a city'

Biden: 'If I had a Ferguson (hic), it would look like a city'

Obama signs executive order renaming 'looters' to 'undocumented shoppers'

Ethicists agree: two wrongs do make a right so long as Bush did it first

The aftermath of the 'War on Women 2014' finds a new 'Lost Generation' of disillusioned Democrat politicians, unable to cope with life out of office

The aftermath of the 'War on Women 2014' finds a new 'Lost Generation' of disillusioned Democrat politicians, unable to cope with life out of office

White House: Republican takeover of the Senate is a clear mandate from the American people for President Obama to rule by executive orders

Nurse Kaci Hickox angrily tells reporters that she won't change her clocks for daylight savings time

Democratic Party leaders in panic after recent poll shows most Democratic voters think 'midterm' is when to end pregnancy

Desperate Democratic candidates plead with Obama to stop backing them and instead support their GOP opponents

Desperate Democratic candidates plead with Obama to stop backing them and instead support their GOP opponents

Ebola Czar issues five-year plan with mandatory quotas of Ebola infections per each state based on voting preferences

Study: crony capitalism is to the free market what the Westboro Baptist Church is to Christianity

Study: crony capitalism is to the free market what the Westboro Baptist Church is to Christianity

Fun facts about world languages: the Left has more words for statism than the Eskimos have for snow

African countries to ban all flights from the United States because "Obama is incompetent, it scares us"

African countries to ban all flights from the United States because "Obama is incompetent, it scares us"

Nobel Peace Prize controversy: Hillary not nominated despite having done even less than Obama to deserve it

Obama: 'Ebola is the JV of viruses'

BREAKING: Secret Service foils Secret Service plot to protect Obama

Revised 1st Amendment: buy one speech, get the second free

Revised 1st Amendment: buy one speech, get the second free

Sharpton calls on white NFL players to beat their women in the interests of racial fairness

President Obama appoints his weekly approval poll as new national security adviser

Obama wags pen and phone at Putin; Europe offers support with powerful pens and phones from NATO members

White House pledges to embarrass ISIS back to the Stone Age with a barrage of fearsome Twitter messages and fatally ironic Instagram photos

White House pledges to embarrass ISIS back to the Stone Age with a barrage of fearsome Twitter messages and fatally ironic Instagram photos

Obama to fight ISIS with new federal Terrorist Regulatory Agency

Obama vows ISIS will never raise their flag over the eighteenth hole

Obama vows ISIS will never raise their flag over the eighteenth hole

Harry Reid: "Sometimes I say the wong thing"

Elian Gonzalez wishes he had come to the U.S. on a bus from Central America like all the other kids

Obama visits US-Mexican border, calls for a two-state solution

Obama draws "blue line" in Iraq after Putin took away his red crayon

Obama draws "blue line" in Iraq after Putin took away his red crayon

"Hard Choices," a porno flick loosely based on Hillary Clinton's memoir and starring Hillary Hellfire as a drinking, whoring Secretary of State, wildly outsells the flabby, sagging original

Accusations of siding with the enemy leave Sgt. Bergdahl with only two options: pursue a doctorate at Berkley or become a Senator from Massachusetts

Jay Carney stuck in line behind Eric Shinseki to leave the White House; estimated wait time from 15 min to 6 weeks

100% of scientists agree that if man-made global warming were real, "the last people we'd want to help us is the Obama administration"

Jay Carney says he found out that Obama found out that he found out that Obama found out that he found out about the latest Obama administration scandal on the news

"Anarchy Now!" meeting turns into riot over points of order, bylaws, and whether or not 'kicking the #^@&*! ass' of the person trying to speak is or is not violence

Obama retaliates against Putin by prohibiting unionized federal employees from dating hot Russian girls online during work hours

Russian separatists in Ukraine riot over an offensive YouTube video showing the toppling of Lenin statues

"Free Speech Zones" confuse Obamaphone owners who roam streets in search of additional air minutes

"Free Speech Zones" confuse Obamaphone owners who roam streets in search of additional air minutes

Obamacare bolsters employment for professionals with skills to convert meth back into sudafed

Gloves finally off: Obama uses pen and phone to cancel Putin's Netflix account

Gloves finally off: Obama uses pen and phone to cancel Putin's Netflix account

Joe Biden to Russia: "We will bury you by turning more of Eastern Europe over to your control!"

In last-ditch effort to help Ukraine, Obama deploys Rev. Sharpton and Rev. Jackson's Rainbow Coalition to Crimea

Al Sharpton: "Not even Putin can withstand our signature chanting, 'racist, sexist, anti-gay, Russian army go away'!"

Mardi Gras in North Korea: "Throw me some food!"

Mardi Gras in North Korea: "Throw me some food!"

Obama's foreign policy works: "War, invasion, and conquest are signs of weakness; we've got Putin right where we want him"

US offers military solution to Ukraine crisis: "We will only fight countries that have LGBT military"

Putin annexes Brighton Beach to protect ethnic Russians in Brooklyn, Obama appeals to UN and EU for help

The 1980s: "Mr. Obama, we're just calling to ask if you want our foreign policy back. The 1970s are right here with us, and they're wondering, too."

The 1980s: "Mr. Obama, we're just calling to ask if you want our foreign policy back. The 1970s are right here with us, and they're wondering, too."

In a stunning act of defiance, Obama courageously unfriends Putin on Facebook

MSNBC: Obama secures alliance with Austro-Hungarian Empire against Russia’s aggression in Ukraine

Study: springbreak is to STDs what April 15th is to accountants

Study: springbreak is to STDs what April 15th is to accountants

Efforts to achieve moisture justice for California thwarted by unfair redistribution of snow in America

North Korean voters unanimous: "We are the 100%"

Leader of authoritarian gulag-site, The People's Cube, unanimously 're-elected' with 100% voter turnout

Super Bowl: Obama blames Fox News for Broncos' loss

Feminist author slams gay marriage: "a man needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle"

Feminist author slams gay marriage: "a man needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle"

Beverly Hills campaign heats up between Henry Waxman and Marianne Williamson over the widening income gap between millionaires and billionaires in their district

Biden to lower $10,000-a-plate Dinner For The Homeless to $5,000 so more homeless can attend

Kim becomes world leader, feeds uncle to dogs; Obama eats dogs, becomes world leader, America cries uncle

North Korean leader executes own uncle for talking about Obamacare at family Christmas party

North Korean leader executes own uncle for talking about Obamacare at family Christmas party

White House hires part-time schizophrenic Mandela sign interpreter to help sell Obamacare

Kim Jong Un executes own "crazy uncle" to keep him from ruining another family Christmas

OFA admits its advice for area activists to give Obamacare Talk at shooting ranges was a bad idea

President resolves Obamacare debacle with executive order declaring all Americans equally healthy

Obama to Iran: "If you like your nuclear program, you can keep your nuclear program"

Bovine community outraged by flatulence coming from Washington DC

Bovine community outraged by flatulence coming from Washington DC

Obama: "I'm not particularly ideological; I believe in a good pragmatic five-year plan"

Shocker: Obama had no knowledge he'd been reelected until he read about it in the local newspaper last week

Server problems at HealthCare.gov so bad, it now flashes 'Error 808' message

Server problems at HealthCare.gov so bad, it now flashes 'Error 808' message

NSA marks National Best Friend Day with official announcement: "Government is your best friend; we know you like no one else, we're always there, we're always willing to listen"

Al Qaeda cancels attack on USA citing launch of Obamacare as devastating enough

The President's latest talking point on Obamacare: "I didn't build that"

Dizzy with success, Obama renames his wildly popular healthcare mandate to HillaryCare

Dizzy with success, Obama renames his wildly popular healthcare mandate to HillaryCare

Carney: huge ObamaCare deductibles won't look as bad come hyperinflation

Washington Redskins drop 'Washington' from their name as offensive to most Americans

Poll: 83% of Americans favor cowboy diplomacy over rodeo clown diplomacy

GOVERNMENT WARNING: If you were able to complete ObamaCare form online, it wasn't a legitimate gov't website; you should report online fraud and change all your passwords

GOVERNMENT WARNING: If you were able to complete ObamaCare form online, it wasn't a legitimate gov't website; you should report online fraud and change all your passwords

Obama administration gets serious, threatens Syria with ObamaCare

Obama authorizes the use of Vice President Joe Biden's double-barrel shotgun to fire a couple of blasts at Syria

Sharpton: "British royals should have named baby 'Trayvon.' By choosing 'George' they sided with white Hispanic racist Zimmerman"

DNC launches 'Carlos Danger' action figure; proceeds to fund a charity helping survivors of the Republican War on Women

DNC launches 'Carlos Danger' action figure; proceeds to fund a charity helping survivors of the Republican War on Women

Nancy Pelosi extends abortion rights to the birds and the bees

Hubble discovers planetary drift to the left

Obama: 'If I had a daughter-in-law, she would look like Rachael Jeantel'

FISA court rubberstamps statement denying its portrayal as government's rubber stamp

FISA court rubberstamps statement denying its portrayal as government's rubber stamp

Every time ObamaCare gets delayed, a Julia somewhere dies

GOP to Schumer: 'Force full implementation of ObamaCare before 2014 or Dems will never win another election'

Obama: 'If I had a son... no, wait, my daughter can now marry a woman!'

Obama: 'If I had a son... no, wait, my daughter can now marry a woman!'

Janet Napolitano: TSA findings reveal that since none of the hijackers were babies, elderly, or Tea Partiers, 9/11 was not an act of terrorism

News Flash: Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-LA) can see Canada from South Dakota

Susan Rice: IRS actions against tea parties caused by anti-tax YouTube video that was insulting to their faith

Susan Rice: IRS actions against tea parties caused by anti-tax YouTube video that was insulting to their faith

Drudge Report reduces font to fit all White House scandals onto one page

Obama: the IRS is a constitutional right, just like the Second Amendment

White House: top Obama officials using secret email accounts a result of bad IT advice to avoid spam mail from Nigeria

White House: top Obama officials using secret email accounts a result of bad IT advice to avoid spam mail from Nigeria

Jay Carney to critics: 'Pinocchio never said anything inconsistent'

Obama: If I had a gay son, he'd look like Jason Collins

Gosnell's office in Benghazi raided by the IRS: mainstream media's worst cover-up challenge to date

Gosnell's office in Benghazi raided by the IRS: mainstream media's worst cover-up challenge to date

IRS targeting pro-gay-marriage LGBT groups leads to gayest tax revolt in U.S. history

After Arlington Cemetery rejects offer to bury Boston bomber, Westboro Babtist Church steps up with premium front lawn plot

After Arlington Cemetery rejects offer to bury Boston bomber, Westboro Babtist Church steps up with premium front lawn plot

Boston: Obama Administration to reclassify marathon bombing as 'sportsplace violence'

Study: Success has many fathers but failure becomes a government program

US Media: Can Pope Francis possibly clear up Vatican bureaucracy and banking without blaming the previous administration?

US Media: Can Pope Francis possibly clear up Vatican bureaucracy and banking without blaming the previous administration?

Michelle Obama praises weekend rampage by Chicago teens as good way to burn calories and stay healthy

This Passover, Obama urges his subjects to paint lamb's blood above doors in order to avoid the Sequester

White House to American children: Sequester causes layoffs among hens that lay Easter eggs; union-wage Easter Bunnies to be replaced by Mexican Chupacabras

Time Mag names Hugo Chavez world's sexiest corpse

Boy, 8, pretends banana is gun, makes daring escape from school

Study: Free lunches overpriced, lack nutrition

Oscars 2013: Michelle Obama announces long-awaited merger of Hollywood and the State

Oscars 2013: Michelle Obama announces long-awaited merger of Hollywood and the State

Joe Salazar defends the right of women to be raped in gun-free environment: 'rapists and rapees should work together to prevent gun violence for the common good'

Dept. of Health and Human Services eliminates rape by reclassifying assailants as 'undocumented sex partners'

Kremlin puts out warning not to photoshop Putin riding meteor unless bare-chested

Kremlin puts out warning not to photoshop Putin riding meteor unless bare-chested

Deeming football too violent, Obama moves to introduce Super Drone Sundays instead

Japan offers to extend nuclear umbrella to cover U.S. should America suffer devastating attack on its own defense spending

Feminists organize one billion women to protest male oppression with one billion lap dances

Urban community protests Mayor Bloomberg's ban on extra-large pop singers owning assault weapons

Concerned with mounting death toll, Taliban offers to send peacekeeping advisers to Chicago

Karl Rove puts an end to Tea Party with new 'Republicans For Democrats' strategy aimed at losing elections

Answering public skepticism, President Obama authorizes unlimited drone attacks on all skeet targets throughout the country

Skeet Ulrich denies claims he had been shot by President but considers changing his name to 'Traps'

White House releases new exciting photos of Obama standing, sitting, looking thoughtful, and even breathing in and out

White House releases new exciting photos of Obama standing, sitting, looking thoughtful, and even breathing in and out

New York Times hacked by Chinese government, Paul Krugman's economic policies stolen

White House: when President shoots skeet, he donates the meat to food banks that feed the middle class

To prove he is serious, Obama eliminates armed guard protection for President, Vice-President, and their families; establishes Gun-Free Zones around them instead

State Dept to send 100,000 American college students to China as security for US debt obligations

Jay Carney: Al Qaeda is on the run, they're just running forward

President issues executive orders banning cliffs, ceilings, obstructions, statistics, and

other notions that prevent us from moving forwards and upward

President issues executive orders banning cliffs, ceilings, obstructions, statistics, and

other notions that prevent us from moving forwards and upward

Fearing the worst, Obama Administration outlaws the fan to prevent it from being hit by certain objects

World ends; S&P soars

Riddle of universe solved; answer not understood

Meek inherit Earth, can't afford estate taxes

Meek inherit Earth, can't afford estate taxes

Greece abandons Euro; accountants find Greece has no Euros anyway

Wheel finally reinvented; axles to be gradually reinvented in 3rd quarter of 2013

Bigfoot found in Ohio, mysteriously not voting for Obama

Bigfoot found in Ohio, mysteriously not voting for Obama

As Santa's workshop files for bankruptcy, Fed offers bailout in exchange for control of 'naughty and nice' list

Freak flying pig accident causes bacon to fly off shelves

Obama: green economy likely to transform America into a leading third world country of the new millennium

Obama: green economy likely to transform America into a leading third world country of the new millennium

Report: President Obama to visit the United States in the near future

Obama promises to create thousands more economically neutral jobs

Modernizing Islam: New York imam proposes to canonize Saul Alinsky as religion's latter day prophet

Modernizing Islam: New York imam proposes to canonize Saul Alinsky as religion's latter day prophet

Imam Rauf's peaceful solution: 'Move Ground Zero a few blocks away from the mosque and no one gets hurt'

Study: Obama's threat to burn tax money in Washington 'recruitment bonanza' for Tea Parties

Study: no Social Security reform will be needed if gov't raises retirement age to at least 814 years

Obama attends church service, worships self

Obama attends church service, worships self

Obama proposes national 'Win The Future' lottery; proceeds of new WTF Powerball to finance more gov't spending

Obama proposes national 'Win The Future' lottery; proceeds of new WTF Powerball to finance more gov't spending

Historical revisionists: "Hey, you never know"

Historical revisionists: "Hey, you never know"

Vice President Biden: criticizing Egypt is un-pharaoh

Israelis to Egyptian rioters: "don't damage the pyramids, we will not rebuild"

Lake Superior renamed Lake Inferior in spirit of tolerance and inclusiveness

Al Gore: It's a shame that a family can be torn apart by something as simple as a pack of polar bears

Al Gore: It's a shame that a family can be torn apart by something as simple as a pack of polar bears

Michael Moore: As long as there is anyone with money to shake down, this country is not broke

Obama's teleprompters unionize, demand collective bargaining rights

Obama calls new taxes 'spending reductions in tax code.' Elsewhere rapists tout 'consent reductions in sexual intercourse'

Obama's teleprompter unhappy with White House Twitter: "Too few words"

Obama's teleprompter unhappy with White House Twitter: "Too few words"

Obama's Regulation Reduction committee finds US Constitution to be expensive outdated framework inefficiently regulating federal gov't

Taking a page from the Reagan years, Obama announces new era of Perestroika and Glasnost

Responding to Oslo shootings, Obama declares Christianity "Religion of Peace," praises "moderate Christians," promises to send one into space

Responding to Oslo shootings, Obama declares Christianity "Religion of Peace," praises "moderate Christians," promises to send one into space

Republicans block Obama's $420 billion program to give American families free charms that ward off economic bad luck

Republicans block Obama's $420 billion program to give American families free charms that ward off economic bad luck

White House to impose Chimney tax on Santa Claus

Obama decrees the economy is not soaring as much as previously decreeed

Conservative think tank introduces children to capitalism with pop-up picture book "The Road to Smurfdom"

Al Gore proposes to combat Global Warming by extracting silver linings from clouds in Earth's atmosphere

Al Gore proposes to combat Global Warming by extracting silver linings from clouds in Earth's atmosphere

Obama refutes charges of him being unresponsive to people's suffering: "When you pray to God, do you always hear a response?"

Obama regrets the US government didn't provide his mother with free contraceptives when she was in college

Obama regrets the US government didn't provide his mother with free contraceptives when she was in college

Fluke to Congress: drill, baby, drill!

Planned Parenthood introduces Frequent Flucker reward card: 'Come again soon!'

Obama to tornado victims: 'We inherited this weather from the previous administration'

Obama congratulates Putin on Chicago-style election outcome

Obama congratulates Putin on Chicago-style election outcome

People's Cube gives itself Hero of Socialist Labor medal in recognition of continued expert advice provided to the Obama Administration helping to shape its foreign and domestic policies

Hamas: Israeli air defense unfair to 99% of our missiles, "only 1% allowed to reach Israel"

Democrat strategist: without government supervision, women would have never evolved into humans

Democrat strategist: without government supervision, women would have never evolved into humans

Voters Without Borders oppose Texas new voter ID law

Enraged by accusation that they are doing Obama's bidding, media leaders demand instructions from White House on how to respond

Obama blames previous Olympics for failure to win at this Olympics

Obama blames previous Olympics for failure to win at this Olympics

Official: China plans to land on Moon or at least on cheap knockoff thereof

Koran-Contra: Obama secretly arms Syrian rebels

Poll: Progressive slogan 'We should be more like Europe' most popular with members of American Nazi Party

Obama to Evangelicals: Jesus saves, I just spend

Obama to Evangelicals: Jesus saves, I just spend

May Day: Anarchists plan, schedule, synchronize, and execute a coordinated campaign against all of the above

Midwestern farmers hooked on new erotic novel "50 Shades of Hay"

Study: 99% of Liberals give the rest a bad name

Obama meets with Jewish leaders, proposes deeper circumcisions for the rich

Historians: Before HOPE & CHANGE there was HEMP & CHOOM at ten bucks a bag

Historians: Before HOPE & CHANGE there was HEMP & CHOOM at ten bucks a bag

Cancer once again fails to cure Venezuela of its "President for Life"

Tragic spelling error causes Muslim protesters to burn local boob-tube factory

Secretary of Energy Steven Chu: due to energy conservation, the light at the end of the tunnel will be switched off

Secretary of Energy Steven Chu: due to energy conservation, the light at the end of the tunnel will be switched off

Obama Administration running food stamps across the border with Mexico in an operation code-named "Fat And Furious"

Obama Administration running food stamps across the border with Mexico in an operation code-named "Fat And Furious"

Pakistan explodes in protest over new Adobe Acrobat update; 17 local acrobats killed

Pakistan explodes in protest over new Adobe Acrobat update; 17 local acrobats killed

White House: "Let them eat statistics"

Special Ops: if Benedict Arnold had a son, he would look like Barack Obama

AD

GOES

HERE

©* 1917 – 2022

The People's Cube, Politburo and Central Committee of the Socialist

Shadow Party, Ministry of Truth, Comrades of Armed Organs, Young Pioneer

Organizations, Komsomol, Society for Sport and Technology, Society for

Advancement of Secondary Sexual Characteristics, and other groups and collectives

of our great Socialist American Motherland.

©* 1917 – 2022

The People's Cube, Politburo and Central Committee of the Socialist

Shadow Party, Ministry of Truth, Comrades of Armed Organs, Young Pioneer

Organizations, Komsomol, Society for Sport and Technology, Society for

Advancement of Secondary Sexual Characteristics, and other groups and collectives

of our great Socialist American Motherland.